After showers is the best chance to easily locate deer tracks in the desert.

Coues deer in small water catchment.

Coues deer in the same small water catchment from the above photo that is dry five days later.

Small area rain can hold.

From approximately July through September, the Southwest experiences a weather pattern known as the monsoon. Although a monsoon is really just a switch in the localized wind patterns, it brings with it thunderstorms that create torrential bursts of heavy rain on a regular basis, often daily.

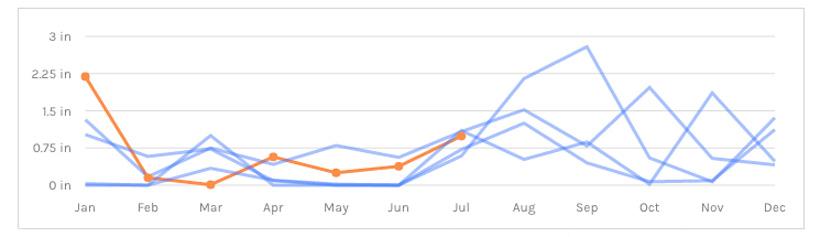

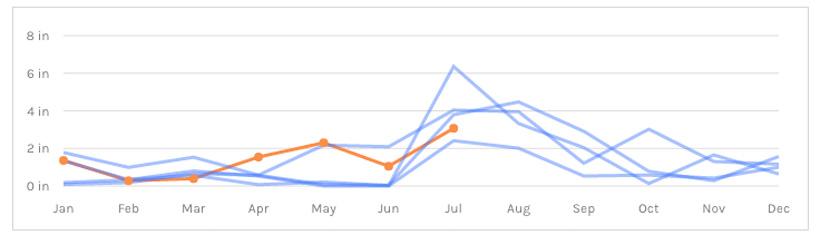

Even in the most arid regions of the Southwest, the monsoon can increase precipitation drastically for a few summer months. For example, take Phoenix, AZ. From April to June, the Phoenix area averages approximately 0.10 inches of precipitation per month. In contrast, from July to September, Phoenix averages almost 1” of rain per month.

A little further north in Flagstaff, AZ., that changes from 0.7 inches per month to almost 3” of precipitation per month, respectively. Historical temperature and precipitation for every unit in each Western state that GOHUNT covers can be found on each Unit Profile on Insider.

The monsoons can be unpredictable with both isolated and scattered showers. As an example, let’s look at Flagstaff, AZ. again. Flagstaff is located for practical purposes in the center of the state. It is located at 7,000’ in elevation and is just south of the tallest mountain peaks in the state with Humphrey’s Peak coming in at 12,633’. In 2012, Flagstaff received 6.30” of rain during the monsoon season; however, in 2013, Flagstaff received 15.70” over the same time period. In both 2012 and 2013, Phoenix—just 144 miles south—received almost exactly 3” of rain. Additionally, over the last 10 years, Flagstaff has averaged approximately 1.5” of rain in September; during that span there were four years when less than an inch of rain fell during the month. Again, the bottom line is that the weather during this time of year is unpredictable.

In many western states, the monsoon season coincides with several big game hunting seasons—most notably archery antelope, deer, and elk. You can generalize the effects of the monsoon on any given hunt during that time of year. If it’s dry, sit water; if it’s wet, don’t focus your efforts on water. Yet, depending on the severity of the monsoon, or lack of one, you can adjust your hunting strategy to get the most of the monsoon’s unpredictable weather. Below are a few ideas to get the most from the monsoon this season.

Across the West, one of the most effective methods to connect on an antelope is to sit water, especially for bowhunters. In dry years, selecting a water source to sit may be easy; however, if the monsoons have rolled through on a consistent basis, water availability may make the decision more challenging. In this case, the key to success is scouting. When scouting, choose vantage points that allow oversight of nearby waters. While glassing, pay close attention to which water sources antelope are using most frequently. If one water source is being used more heavily, set up a blind there to hunt throughout the season. If possible, identify two or three water sources so that you have a backup or two. If spot-and-stalk is your preferred method, don’t discount sitting in a blind over water during the middle of the day. Antelope are likely to go to water during mid-day hours where you may connect while taking a break from morning and afternoon stalks.

Out of all western big game species, the mule deer may be the most difficult to hunt over water. This is because mule deer have a higher tendency to drink less often than other species and do so mostly under cover of darkness. That being said, mule deer are still highly dependent on available water. This is especially true in the arid regions of the Southwest. While the monsoon may not affect mule deer hunting in the northern regions or mountainous regions of the Southwest, the same is not true of the desert regions. If one can endure the elevated temperatures of the desert during monsoon season, you may have a slight advantage. First, it’s safe to say that mule deer—bucks included—will be close to a water source, regardless of how limited they may be in a given region. Glassing areas near water sources that offer good daylight shade and bedding cover may unveil a big buck.

Second, mule deer leave tracks and there is no better place to track a big mule deer buck than in the desert after a monsoon shower. Tracking may lead to the discovery of travel patterns or it may lead you right to the buck-of-a-lifetime.

The Coues deer is notorious for either drinking from small pools of water or by getting a large portion of their water requirements from browse. Because of their small body size combined with less daylight movement in late summer, the Coues deer requires little water. For these reasons, hunting near a water source like a cattle tank or wildlife guzzler it not as critical when hunting Coues deer.

While scouting, look for any small depressions or low areas that look like they could potentially hold water after a few solid rains. If the monsoon rains have already fallen, find a spot that holds water and deer tracks; hang a stand or set a ground blind. If spot and stalk is your preferred hunting method, look for areas of heavy cover where browse is likely to hold more water on its exterior after a shower and hunt there after a storm has passed. In the desert, Coues deer rely heavily on cactus species for water intake; for example, the fruit found on the barrel cactus, when available.

Elk rely more heavily on water than any other Southwestern big game species, especially bulls during the rut. A bull will wallow almost every day during the rut, if possible. Additionally, rut-weary bulls will seek out water on a regular basis; perhaps multiple times during the day during the heat of rut activity.

During dry years when the monsoons have missed your hunting unit, sitting over water can be your best bet at a trophy bull, especially if water sources are few and far between. If showers have initially filled up most of the tanks in the area, but those have now dried up, it becomes a little more challenging. In this case, bulls may have several options. Your best bet is to put some time in scouting to see if you can tell which water sources are being used more heavily and which ones are being used by bulls. Sitting water may be less effective under this scenario, but sitting water during the middle of the day or early afternoon instead of taking a nap at camp may be just the opportunity needed to take a great bull. If nothing materializes, but rut activity—bugles—occur, do not hesitate leaving the water to chase the bugles.

Finding wallows can be difficult. One can look in drainages that often hold water or find low spots on even ground. Unfortunately, there is no real science to finding where a bull might choose to cool off. During wet years when the roads are muddy, a bull may take an afternoon roll in the muddy water right in the road. While driving to and from your hunting locations, look hard at big pools of water in the road. It’s pretty easy to see the marks made in the mud by an 800 lb. animal with impressive head gear.

The immediate—up to 24 hours—after a heavy rainfall provide perfect stalking conditions. Soaking monsoon storms can dampen even the noisiest ground cover, such as leaves, sticks and pine needles and cones. Take advantage of a soaking storm by getting the wind right and sneaking into a herd of unsuspecting elk. This is obviously easiest if the elk are vocal, but often, after a storm, elk may be less vocal or completely quiet. If the bugles stop, slowly move through elk habitat that you know elk tend to use based on your scouting or previous hunts.

In most cases, the monsoon brings with it much needed rain. Across the West, some locations receive almost half of their annual precipitation during the monsoon season; however, the monsoons also bring with it a few hazards, including dust storms, lightning, torrential downpours, and flash flooding. You can only make the most of the monsoon by staying safe. Below are a few thoughts on monsoon safety.

Actively monitor the weather on a mobile app or radio.

Avoid hunting during severe storms.

Dress appropriately and carry rain gear in your pack.

During lightning storms avoid:

Open locations.

High places, such as hilltops and ridgetops.

Tall, isolated trees.

Water.

If stuck in a lightning storm, find protection in lower vegetation, such as saplings or underbrush.

Never cross flooded roadways or stream and river crossings.

Remember, flooding can be worse in burned areas without much ground cover.