Photo Credit: Terrierman

When do you think the hunting fee system started? And why did it start?

The short answer is that hunting licenses originated hundreds of years ago, and they were designed to essentially discriminate against non-residents of a state. (We Americans clearly have a lot of state pride…)

Over time, however, hunting fees have become a pivotal factor in shaping our country’s environmental health, and have ultimately become the most substantial source of funding for wildlife conservation efforts in the United States.

It all dates back to colonial America.

The original intent behind hunting licenses was not necessarily the welfare of wildlife, but rather the discrimination against non-state-residents. States were bound and determined to preserve their land, and all that implied, for their own residents. And to ensure that no one else infringed upon their property, the states introduced a number of laws that protected what they believed was rightfully theirs.

In 1719, for example, New Jersey introduced a law prohibiting non-residents from taking oysters or putting them on board a vessel not owned by a resident.

Similar discrimination is also found in a game law enacted in North Carolina in 1745, which stipulated that non-residents were required to present a certificate proving that they had planted and tended 5,000 hills of corn the preceding year, or season, in the county where he wished to hunt. This law was later amended to deny hunting rights to individuals who did not own 100 acres of land or had not tended 10,000 corn hills in the state during the previous year.

In 1840, Virginia introduced laws prohibiting non-residents from hunting wild fowl on certain beaches or marshes.

And in 1854, North Carolina prohibited non-residents from hunting wild fowl, explaining that:

“…large numbers of wild fowl collect during the fall and winter, in the waters of Currituck County, which are a source of great profit to the inhabitants thereof; and whereas, persons from other States, not residents of this State, shoot and kill, decoy and frighten the same, to the great annoyance and detriment of the citizens of our own State: Now Be it enacted…” (Public Laws of the State of North Carolina, passed by the General Assembly in 1854)

States viewed local wildlife not only as their property, but as a financial asset for their citizens.

As such, the laws acted as a sort of economic protection plan for the state and its residents. But while absolute prohibition may have safeguarded the state from encroachment, it did not take full advantage of the financial opportunity at hand. This would change with the advent of non-resident hunting fees.

The first law containing a non-resident license provision was likely that passed in 1873 in New Jersey under the title, “An Act to Incorporate the West Jersey Game Protective Association”. This act stipulated that non-residents were required to procure a membership certificate before hunting. The membership fee was a fixed amount of $5 for the first year and $2 per year thereafter. It was these certificates that essentially became non-resident licenses.

It was not long before a number of other states adopted the same idea, allowing non-residents to pay a fee in order to hunt on the state’s land.

The development of resident licenses, on the other hand, was a little slower to take shape.

The origination of resident hunting licenses starts with the system of special licenses introduced in some counties of Maryland in the 1870s and 1880s. These special laws stipulated that shooting wild fowl from sink boxes, sneak boats, or in some cases, from blinds, was unlawful except under license. And these licenses were only available to residents.

The first of these special laws was passed in 1872 in the Susquehanna Flats region of Chesapeake Bay, and provided that:

“…no owner, master, hirer, borrower, employee of any owner, or other person, shall use or employee any sink box, or sneak boat of any description whatever, for the purpose of shooting at wild water-fowl…without first obtaining a license to so use and employee…” (The Maryland Code: Public Local Laws: Adopted by the General Assembly in 1872)

Over the next two decades, special license laws became increasingly prominent, employed by counties that wished to protect their wildlife.

But it wasn’t until 1895, when Michigan took measures to restrict the killing of deer, that a system of general resident hunting licenses appeared. Michigan legislation stipulated that residents would be charged a nominal fee of 50-cents while non-residents would charged $25 to procure a license for hunting deer.

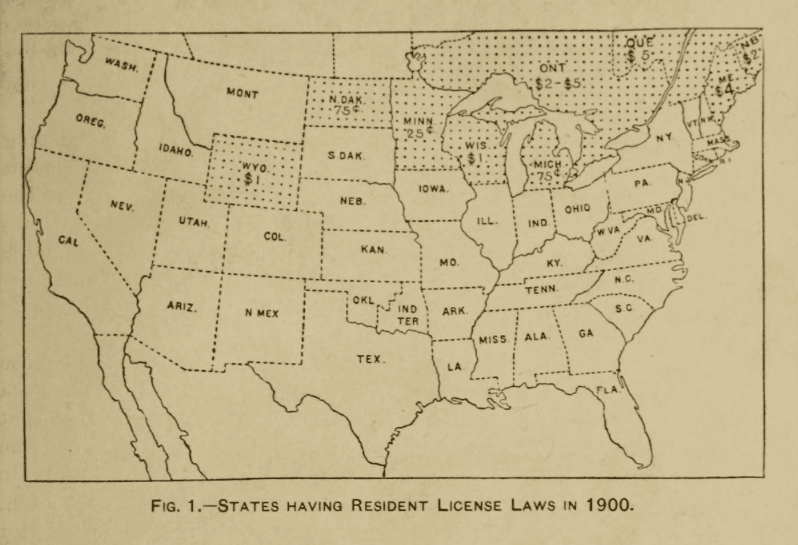

A year later, Hawaii passed a law establishing a $5 hunting license for the island of Oahu. And in 1897, Wisconsin introduced legislation charging residents a fee of $1 and non-residents a more substantial amount. Then it was North Dakota, Maine, South Dakota and Nebraska. These states and many more followed suit, introducing their own resident and non-resident licensing systems.

Initially, these licenses were only required for hunting big game.

But by the beginning of the 20th century, there was a growing tendency to give protection to smaller game as well. States were also beginning to call attention to state preserves, which they believed would be another important factor in game protection.

When it comes to hunting, two of the most pertinent challenges of game protection and conservation have always been: 1/ how to enforce the laws, and 2/ how to secure the funds necessary to do so.

Because the truth is, legislation alone is not enough.

As history has shown, rules must be enforced, and serious efforts must be made to secure compliance with the law. By acting like a direct tax on those who hunt, license fees provide the funds to carry out these services.

While each state may have its own license and fee structure, issuing tags and permits for a certain number of animals at a certain time of year, the importance of the system is universal.

Hunting fees keep conservation efforts alive, and ultimately help wildlife thrive. And at the end of the day, let us not forget, hunting is a privilege, and in a way, licenses help to ensure it remains that way.